We’ve written literally millions of words about motorbikes here at SuperBike over the years. Probably around 15 million in fact (about 30,000 words an issue, twelve or thirteen times a year, for nearly 40 years, plus internet, Twitter, Facebook.) Words about brakes, engines, paint schemes, attractive women, racers, helmets, radiators, underseat tool kits and Napoleon Bonaparte.

Not much about gearboxes though. That’s anecdotal of course: I’ve not (yet) managed to index every word on every page in a searchable database. One day though… But based on a ‘seat of the pants’ estimate, there’s probably one feature in five hundred about transmissions.

BMW K1200 gearbox. Clutch goes on the left hand side, black cylinder on the right is the shaft drive housing

Which is both surprising and unsurprising in equal measure. They’re important things, gearboxes. But like gravity, ATP synthesis and functioning sewers, they don’t get much attention unless things go wrong. People spend thousands of pounds on trackday bikes: bolting on unobtanium exhausts at exorbitant prices, plugging in small ECU computers and dataloggers which could run a mission to Mars, and upgrading suspension and brakes like there’s no tomorrow. But for most people, their ‘umble gear clusters lie hidden, in the dark. Unmolested by the white-hot upgrade technology applied elsewhere.

Part of it is, no doubt, out of sight, out of mind. And, of course, most modern bikes have fabulous gearboxes, which rarely give trouble, and can stand up to a lot of abuse. The final drive, out on show, is the sole part of most people’s upgrades: gorgeous golden chains, with anodised aluminium sprocketry looks great, cuts weight and power losses, and lets riders fiddle with the final drive ratios, to help suit different tracks.

But still. All the power and torque in the world is no use unless you get it to the back wheel. And as the rise of quickshifters has shown, a tiny improvement in every gear change adds up to a lot, particularly at twisty racetracks, where there are hundreds of gear changes in even a short session.

So what’s inside a bike gearbox? Well, see above. At its simplest, there are two shafts: one input shaft connected to the crankshaft via the clutch and one output shaft attached to the final drive sprocket (or shaft bevel-drive box). On these thick, tough, steel shafts are pairs of gears. Like on a pushbike, varying the numbers of teeth on the pairs of gears either multiplies, or reduces the ratio of rotating speeds between the crankshaft and the rear wheel. Lower gears (first, second) let the crankshaft turn more often for every rotation of the rear wheel. So, as on a pushbike, there’s less effort (torque) needed at the crank for every turn. The gearbox multiplies up the torque from the crank, giving more torque at the wheel, meaning more force(thrust) pushing you and your bike along. In a low gear you can pedal your bike up a hill, slowly. The thrust needed at the pedals is less, so your little legs can manage it. But you need to turn the pedals more times for the same distance travelled.

As the engine reaches its rev limit, the situation needs to be reversed. You want to reduce the ratio between crank and wheel, so change up to a higher gear. Now, the crank is turning less often for every rear wheel rotation. The torque is multiplied less, meaning there’s not as much thrust at the tyre, but the wheel can be spun at a higher speed before the engine hits the redline. To continue the pushbike analogy, you’re pedalling downhill now, so the force needed at the pedals is less, but your legs can’t move fast enough. Selecting a higher gear means pushing harder, but with fewer pedal revolutions for the same distance.

When bikes were first built, the transmissions were rudimentary, or even non-existent. A direct drive, with a leather belt, from crankshaft to rear wheel gave one gear, no clutch, and limited performance. Then, as the years passed, clutches appeared, allowing the engine to be disconnected from the rear wheel, and gearboxes were used, to give a wider range of road speeds from the limited engine speeds. Three-speed boxes were common in the early part of the 20th century, then four, five, and eventually six speeds became standard. Increasing the number of gears improved performance, because the rider could match the road speed more precisely to the relatively narrow range of engine speeds where the best power was available. If you could keep the engine within the rev range where peak power was made, without dipping down or reaching up into low-powered engine speeds, then you got maximum acceleration.

Check the cam slots cut into the shift drum (at the top of the pic) on this Nova Racing cassette gearbox

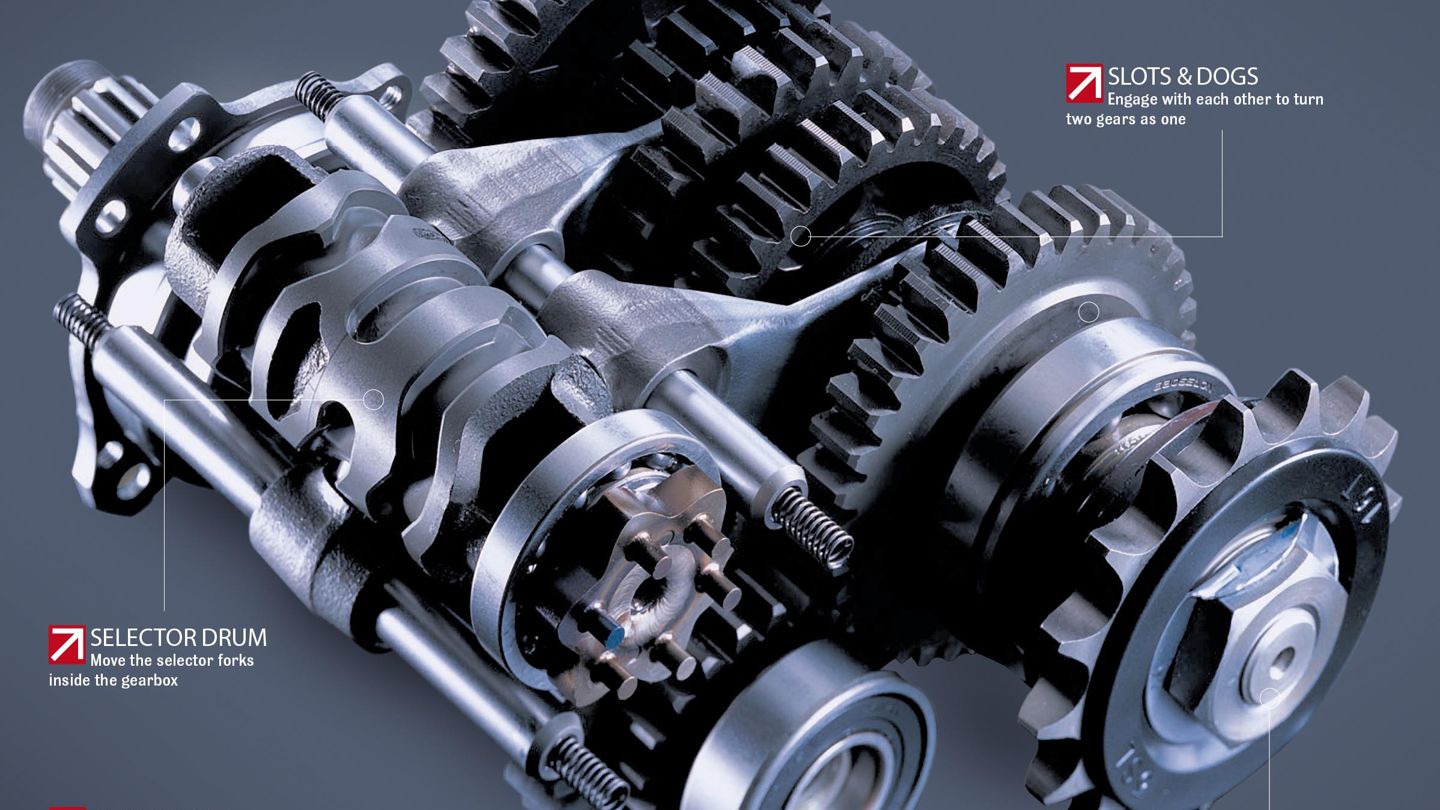

So we have our different gear ratios on the shafts. But we need to be able to choose between them. Hence we need a selector mechanism. On most bikes, that means moving selector forks, which are controlled by cams in a selector drum mechanism. As you move the gear lever, the selector drum turns, and the cam shapes cut into it move the forks from side to side. The forks are engaged into slots in the pairs of gears, and when they move, they slide the different gears along the shafts, locking them together, and selecting a ratio.

Selector forks clearly show here – the two ‘C’-shaped pieces. They’re normally a bit shallower than on this Nova dog-ring gearbox

On our pics, you might notice that all the gears are engaged with each other. That’s because this is a ‘synchromesh’ gearbox. The gears aren’t changed by moving the drive cogs into and out of alignment with each other. Rather, they’re always aligned together, but are locked and unlocked to the drive shafts as they’re slid along by the selector forks. ‘Dogs’: thick bumps on the sides of the gear wheels engage against mating dogs on other gears, and when the gears are slid along, these dogs lock them into gears which are solidly mounted to splines on the gear shafts. Locking different pairs of gears together with the dogs engages different pairs of spinning gears onto the input and output shafts to give your six speeds in the gearbox.

These Yoshimura race kit gears show the dogs, as well as the inner splines on the locked gears pretty well. Note the smooth unsplined inner face on the smaller dog gears – these are the ones that spin freely on the shafts till the dogs lock onto a splined gear, which then firmly locks it onto the shaft.

So, that’s what goes into a bike gearbox, pretty much. The question then is, why would you need to mess about with it? It’s obvious why you’d fit an exhaust or better brakes. How can you get better performance from your transmission?

Who better to ask than the guys at Nova Racing (www.novaracing.com)? Nova’s been building its own performance transmission parts and upgrades for more than 25 years now, and the firm makes most of the gearboxes you’ll see in TT, BSB and even WSB. Based in a small leafy Sussex village called Partridge Green, the firm was started up by a pair of bike-mad engineers, Graham Dyson and Martin Ford-Dunn, initially working to provide replacement gearbox parts for racers. Martin was the blue-sky tech guru, and Graham turned the big ideas into metal. They made the parts which techs and riders in the paddock were crying out for – stronger upgrade parts, or even just replacement parts that the bike firms weren’t providing.

Jeff Claridge is Martin Ford-Dunn’s son-in-law, and he works at the firm now. “In the early days, everything was for racing,” he told us. “Some of our products are used on the road, but is was all originally for competition. We were converting four-speed boxes into five- or six-speed gearboxes, and making replacement stock parts that you just couldn’t get hold of.”

Through the 1990s Nova developed its product range, moving away from ‘proper’ race bikes like the RG500s and TZs of the 1970s and 80s. Racing was much more production-based now, and the gearboxes were less suited to race use. “People moved into production-based racing, using tuned road bikes and making them into superbikes. The ratios weren’t suitable for racing at all, so Nova got more work from teams racing those. And eventually there was more power coming out, so they had to make stronger gearboxes too,” said Jeff.

Cutting gears from scratch lets Nova have total control over materials and design. The gold part is the cutter, the gear being made is the silver part in the centre, covered in cutting oil

Nowadays, Nova’s still hard at it, improving production-based gearboxes for racing. And it’s got an impressive list of clients. From BMW teams in WSB, down through GB Moto in BSB and Padgett’s at the TT, they all rely on Nova transmissions. Indeed, Nova’s doing better than ever at the TT in recent years says Jeff. “We had a bike on the podium in every single class in 2014 (except the TT Zero electric race). That included sidecars as well.”

That Manx success also saw the fastest-ever TT lap with Bruce Anstie on the Padgett’s bike, as well as Michael Dunlop’s BMW S1000RR – all using the good kit from Partridge Green…

But Nova’s still coming up with new ideas, responding to what racers want and need. “We’ve been working with GB Moto on a new dog ring gearbox for the ZX-10R,” says Jeff. “it’s different enough that it catches people’s eye, and it meets the rules and regulations for BSB racing.”

It’s not easy though, treading a fine line between the rules, finances, and new developments. “We’re quite small really, we have a team of twelve people making up to 20-30 gearboxes a month. We’re a lovely little English business success story and I don’t think we get a lot of help with that. If we couldn’t keep going, we’d be missed!”

For 99 per cent of riders on the road, the stock gearbox will be enough. But if you’re rebuilding your motor, maybe adding a load more power from a big-bore kit, or a turbo, then you might want to add some insurance in the transmission. Renovating an older bike, like a 1980s two-stroke? Nova can give you stronger replacements for worn-out stock parts, often for less than original parts would cost (if you could find them). Then there’s a whole range of bikes which have five-speed boxes, but can be uprated to six gears. Yamaha’s FJ1200, FZR1000 and Thunderace for one, as well as several other older designs. Then there’s the hardcore racers, who want a selection of ratios that are closer together, to better suit the narrow powerband on a tuned old-school race motor. Or even, for the truly committed, the ability to select different ratios for every gear in the box, for the ultimate track setup.

Finally, if you’re daft enough to be fitting a bike engine into a project car build, Nova can help with reverse gear conversions and much stronger gearboxes to deal with the extra abuse encountered there.

Real world gear care

- Keeping your gearbox in good order is fairly simple to be honest. There’s no real maintenance associated with it other than the usual engine stuff – keep changing the oil at least on the recommended intervals, or sooner. Use only good-quality oil of the recommended grades. Make sure you use motorcycle oil – car oil isn’t designed to be used in wet clutches or gearboxes, both of which most bikes use.

- Looking after the clutch will also help with gear changes. If you’re hard on the clutch, you might need to check the plate wear more often. Keep the cable properly adjusted, or the hydraulic circuit bled.

- Finally, a poorly-adjusted final drive chain can wreck your gearbox, or make it feel much rougher. A too-tight chain puts a strain on the gearbox output shaft bearing, eventually killing it.

- Properly installed quickshifters shouldn’t harm a gearbox either. But fluffed gear changes – from ham-fisted riding, or a faulty quickshifter – can damage the dogs inside the transmission, or bend the selector forks. In the long run, serious engine damage can come from worn gears, and in the worst case, metal chips can lock up the gearbox completely. Nasty.